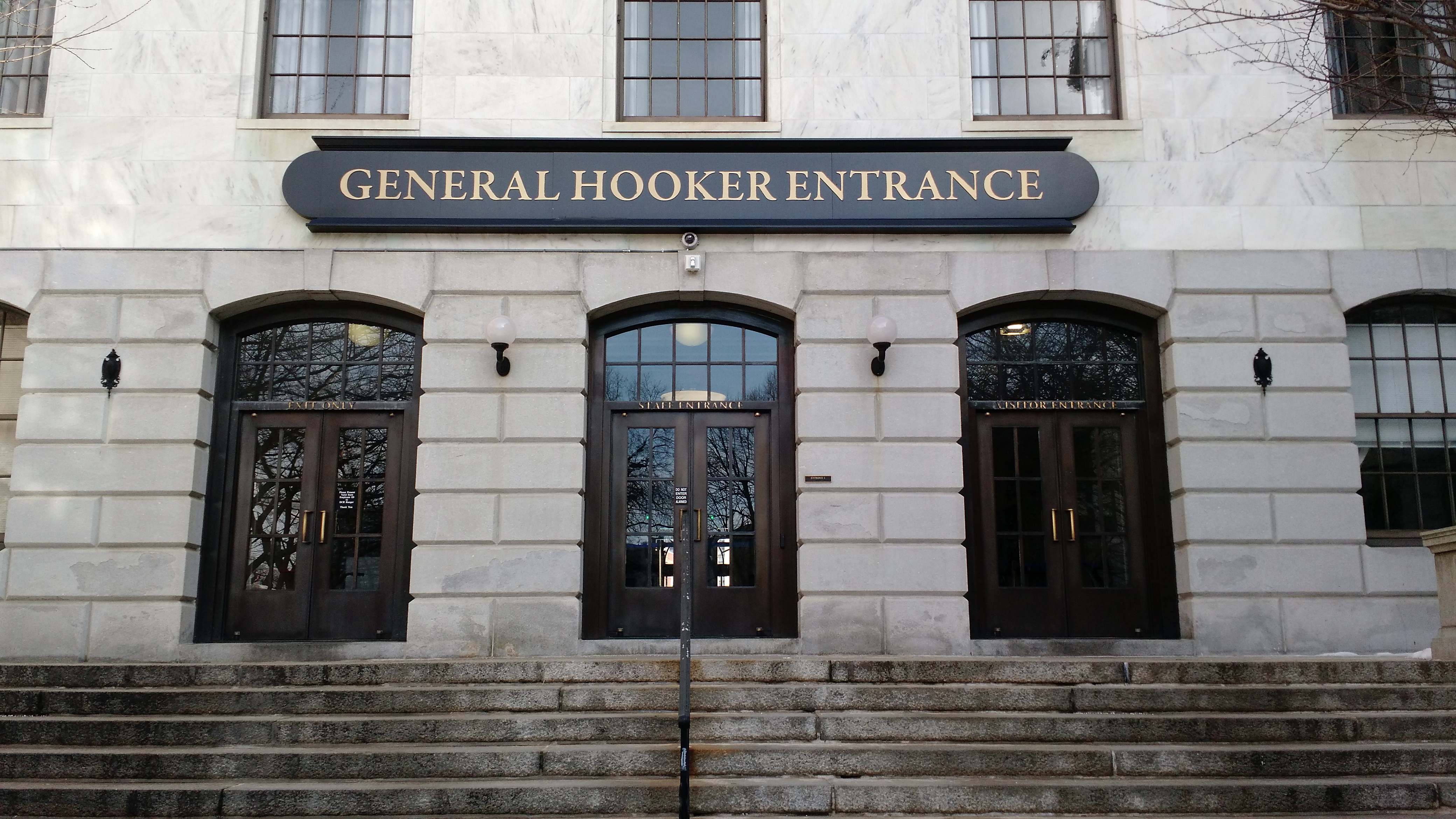

The sign at the most-used entrance to Boston’s State House wouldn’t have caused generations of snickers had it simply honored Gen. Joseph Hooker by including his first name.

Instead, the hometown of patriots got this.

It has stood the time as otherwise sober Bostonians mostly became junior high school students again, but time’s up, a state representative says.

Michelle DuBois says the sign is divorced from any historical context, which could be provided by simply adding Hooker’s first name.

“Some people say, “I’m not a general hooker, I’m an elite hooker. Where is the entrance for me?’ So these types of jokes … kind of bring in this whole other ickiness,” DuBois tells the State House News Service.

Not surprisingly, the idea was met with a hearty guffaw, Boston Magazine says.

And history is a funny thing. Hooker, who commanded the Army of the Potomac, wasn’t that great of a general, and maybe not much of a Bay Stater either.

…according to Peter Drummey, librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the decision to build the Hooker statue along Beacon Street was contentious even before it was erected in 1903. Those who supported it noted that he was born in Hadley and led a large contingent of Massachusetts soldiers in the war, Drummey says.

But those who opposed it argued that Hooker wasn’t all that good of a general (he’d lost a major battle to Gen. Robert E. Lee), he didn’t have a particularly strong a connection to the state, and—and this is an important one—there had been salacious (and unproven) rumors about prostitutes hanging around Hooker’s headquarters, back when everyone gossiped about the exploits of the nation’s top generals.

Contrary to a somewhat popular belief, the word “hooker” as a synonym for “prostitute” does not refer to the general, and had been in use long before he became well-known. So his lewd-sounding last name certainly didn’t help matters. “There was a distaste for him and his personal morals,” Drummey says. “So people right from the time when the statue was put up there, there was this play on words.”

Charles Francis Adams Jr., a Civil War veteran and onetime president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, hated the Hooker monument so much that when he passed by the section of the State House where it was built, according to Drummey, “He would walk on the opposite side of the street so he wouldn’t have to walk near the statue, because he held General Hooker in such low regard.”

Hooker spent his later years in New York, which should be ample enough reason to remove his name from a Boston landmark.