Not surprisingly, PBS’ documentary, “The Vietnam War” is getting more and more difficult to watch from episode to episode.

Sunday night’s episode — Things Falling Apart — focused on the Tet Offensive and the siege of Hue. It included a discussion of this photo:

“It’s the only moment in the film in which we get truly meta,” Burns tells the Washington Post’s podcast that is accompanying “The Vietnam War.”

Burns and his colleague, Lynn Novick, used rarely seen NBC video of the shooting, including the beer the executioner — Nguyen Ngoc Loan — had afterward to celebrate.

But more importantly, the way Lem falls. The way the blood gushes up 8 or 10 or 12 inches from his head for a moment. The way a pool of blood — and NBC, to their credit, insists that we only use exactly what was being shown. No more, and more importantly no less for those of us uncomfortable by that sort of stuff.

We had an internal screening of this episode a few years ago and we had at that point a young intern named Frank, and Frank came down, as is the case in every screening everybody has a chance to say something, and he was clearly upset and he said: I’ve grown up with violent images. I’ve watched TV shows and movies and comic books and graphic novels, and mostly the video games that young boys of his age have played all their lives, violent video games that as a father of a daughter I thank God everyday that they have not had that.

And he said, “But that guy’s really dead,” and he started to cry.

And at that point I just sort of said, “This is a real film we’re making.” We all nodded and comforted him and said, “Yes, he is dead,” and I just thought, as we wring our hands with safe arguments without any empirical data that our kids are different and they’re numbed and enured, that somehow that footage in that photograph got through to one kid. And I’ve seen it in other places, not as profoundly as our Frank, but it made a big difference.

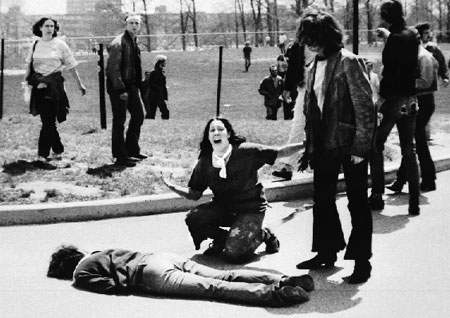

Burns says — correctly — that the image is one of the very few still photographs that changed the war. This is the other one:

“It’s easy to distance yourself from a dead body,” Novick tells the Post of the execution photograph. “Although you shouldn’t, because one should think about who was that person and what happened to them and how did they die. Out of respect we should never not think about those questions of the humanity of a corpse. But here’s a living person who’s dying in that moment. So they’re not dead yet, so you can’t just walk away. You can’t just look away.”

The accompanying video is gruesome enough. The photograph, she says, doesn’t go away.

“I think you have a chance to really contemplate what’s happening and what happened before and what’s happening in that moment, what’s going to happen after, in a different way because it’s a still photograph. And there’s no better or worse, it’s just, they’re different,” she said.