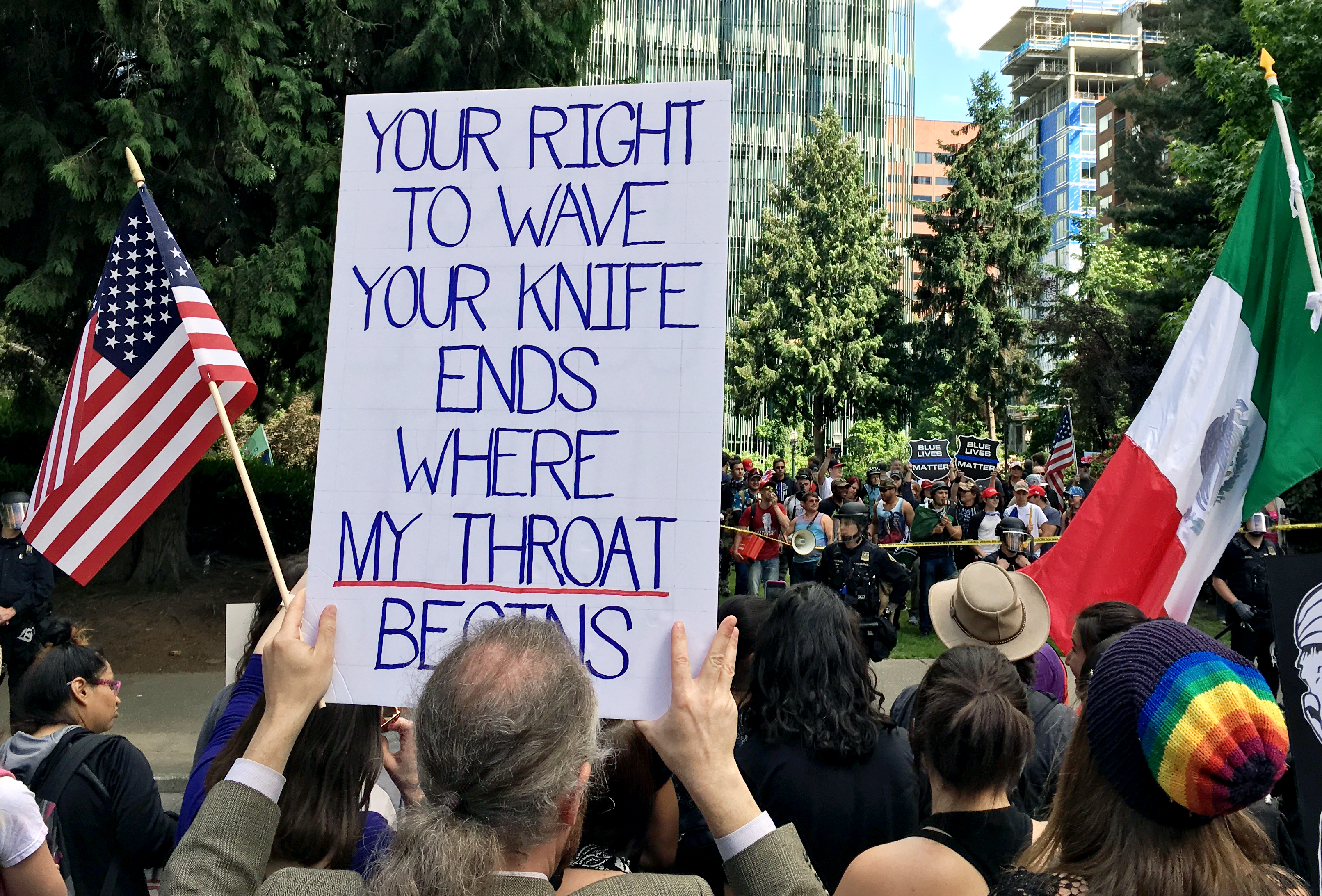

The aftermath of the terrorism in Charlottesville, Va.,has presented the greatest challenge to support for the breadth of the concept of free speech in years, and it appears to be softening.

Both the New York Times and the Boston Globe today carry calls to clip its wings somewhat after the American Civil Liberties Union fought for the right of Nazis and white nationalists to march in Virginia.

“Sometimes even a free speech fanatic like me is forced to admit that the correct answer is ‘shut up,’” Globe columnist Hiawatha Bray writes.

Last week, Bray penned a defense of the free speech rights of former Google engineer James Damore, who wrote a memo his colleagues didn’t like, as he characterized it.

But enough free speech is enough. Bray is applauding the decision by internet providers to oust the Daily Stormer, the pro-Nazi web site, which is returning to the “dark web.”

It might sound like an about-face for me, the guy who teed off on Google just last week for firing employee James Damore because he wrote a memo his colleagues didn’t like. Where’s my reverence for freedom of expression?

It’s right here, strong as ever. I’m pretty nearly an absolutist about such things. I favor the free expression of pretty much all opinions, even bigoted and hateful ones. But if it’s your view that your opponents ought to be killed, it’s time to shut you up.

This is a long way from James Damore’s memo, which suggested that biological differences between men and women may explain Google’s diversity problem. Controversial? Immensely. Hateful? Not even a little bit.

Even so, Google had a right to fire him for writing it. I just think it was a dumb and perhaps dangerous thing to do, because it called into question Google’s regard for the open exchange of ideas. Remember that Google has a near-stranglehold on our access to Internet information. If such a company would fire a man merely for writing a controversial memo, what’s to stop it from shielding all of us from “bad ideas”? For our own good, of course.

The Daily Stormer situation is quite different, on multiple levels. First, neither Google nor GoDaddy have the power to drive this site from the Internet altogether. There are plenty of other domain hosting services where the Stormer can peddle its poisons.

Meanwhile, in a New York Times op-ed, K-Sue Park, a housing attorney and the Critical Race Studies fellow at the UCLA. School of Law, wants the ACLU to rethink the protections of the First Amendment.

Park, a former volunteer with the ACLU, says the organization’s support for the First Amendment is dangerous because it doesn’t protect all people equally.

The question the organization should ask itself is: Could prioritizing First Amendment rights make the distribution of power in this country even more unequal and further silence the communities most burdened by histories of censorship?

This is a vital question because a well-funded machinery ready to harass journalists and academics has arisen in the space beyond First Amendment litigation. If you challenge hateful speech, gird yourself for death threats and for your family to be harassed.

Left-wing academics across the country face this kind of speech suppression, yet they do not benefit from a strong, uniform legal response. Several black professors have been threatened with lynching, shooting or rape for denouncing white supremacy.

Government suppression takes more subtle forms, too. Some of the protesters at President Trump’s inauguration are facing felony riot charges and decades in prison. (The A.C.L.U. is defending only a handful of those 200-plus protesters.) States are considering laws that forgive motorists who drive into protesters. And police arrive with tanks and full weaponry at anti-racist protests but not at white supremacist rallies.

Park says the ACLU’s unwavering support for free speech presumes that all radical views are equal.

In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court was unanimous when it declared unconstitutional a St. Paul ordinance restricting symbols of hate in the form of a burning cross on the lawn of a black family on Dayton’s Bluff. It was a seminal free speech case.

Nonetheless, Justice Byron White advocated the idea that restrictions on hate speech could restrict “only the social evil of hate speech, without creating the danger of driving viewpoints from the marketplace.”

He joined the judgment, he said, “but not the folly of the opinion.”

Twenty-five years later, and 15 years after his death, White is picking up some supporters.

Related: The case against free speech for fascists (Quartz)

City Issues Permit For ‘Free Speech Rally’ On Boston Common (WBUR)