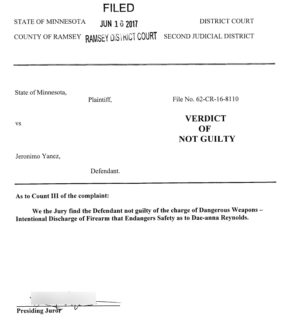

When some of the jurors left the Ramsey County Courthouse after today’s not guilty verdict in the killing of Philando Castile, they looked scared that you might find out their name and where they live. Most didn’t want to talk and who can blame them? For many people, they are the least popular people in the Twin Cities.

There seems little question that they were aware of the consequences of whatever verdict they came up with in the trial of former police officer Jeronimo Yanez. The justice system does not well serve African Americans killed by police.

There seems little question that they were aware of the consequences of whatever verdict they came up with in the trial of former police officer Jeronimo Yanez. The justice system does not well serve African Americans killed by police.

Defense attorneys have an easy time condemning those who cannot defend themselves. Michael Brown stole cigarettes. Freddy Carlos Gray Jr., carried an illegal switchblade. Darius Graves allegedly held up a restaurant. Tony Robinson allegedly assaulted two people. Tamir Rice had a gun. A toy gun.

But Philando Castile only had a broken tail light, a wide-set nose, a gun he was carrying legally, and a little jar of pot under the seat. That, and a cop who cried on the stand, was all Yanez’ attorney needed to cast reasonable doubt on the charge of second-degree manslaughter in the death of a man whose students at the school where he worked adored him.

Add this verdict to the evidence that it’s nearly impossible to obtain a conviction of a police officer for killing an African-American in the United States. The law allows police to shoot if they’re afraid or feel threatened. It’s a lousy system.

But the jury got it right, because that system wasn’t on trial.

The prosecution, surprising in how few witnesses it presented, didn’t enter a critical Yanez interview with the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension into evidence, and relied mainly on the testimony of Diamond Reynolds, who videotaped the aftermath of the shooting on Facebook, in which we all got to see Castile take some of his last breaths.

Video could neither save Castile nor convict Yanez. Video hasn’t been enough to do so since the day Michael Slager took aim at a man running away after a traffic stop, and squeezed the trigger, killing Walter Scott. And it was all on video.

A jury deliberated for only 14 hours, then decided they just couldn’t figure out if there was enough evil intent to justify a murder charge.

That and dozens of other cases provide all the evidence a reasonable person needs to conclude the system doesn’t work for African Americans.

But that system wasn’t on trial in St. Paul.

A prosecution expert testified that Yanez handled the stop incorrectly, not ordering Castile to put his hands on the dashboard, for example. The defense countered with its own expert who said he handled the stop appropriately. One side said Castile had his hand on a gun. The other said he was reaching for a wallet.

The jury spent four days trying to determine if Yanez showed “culpable negligence”. It couldn’t, even though it had to be at least somewhat tempting to indict the system if only to show that African Americans can get justice in the American judicial system.

But that system wasn’t on trial in St. Paul.

Philando Castile shouldn’t be dead. Jeronimo Yanez shouldn’t be a cop, a fact proven by the fact that the St. Anthony Police Department announced immediately after the verdict that he won’t be back on the force.

If the jurors fear you’ll find out who they are, it’s only because they did exactly the job we asked them to do.

“There has always been a systemic problem in the state of Minnesota, and me thinking, common sense that we would get justice,” Castile’s mother, Valerie, told reporters after the verdict. “But nevertheless the system continues to fail black people.”

She’s not wrong.

Neither was the jury.