The new Pew Research survey on religion in American life — the first since 2007– suggests the United States is becoming less religious.

That’s the headline anyway although it may overstate the shift from belief in a god.

There’s been no change in the belief in God from those who are “religiously affiliated.” Ninety-seven percent believed in 2007. Ninety-seven percent believed in 2014.

But the percentage of those who consider themselves “religiously affiliated” has dropped from 83 to 77 percent, Pew says. But it’s important to consider that some component of the drop could be the result of disagreement with an institution rather than a belief on whether there’s a God.

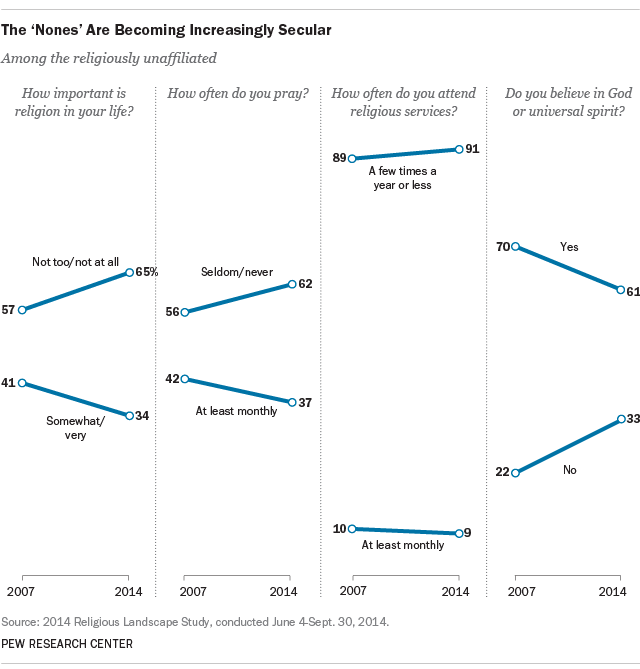

Among the religiously unaffiliated, for example, 61 percent believe in God, according to the survey. That’s down from 70 percent in 2007.

The vast majority of Americans, however, continue to identify with some religious faith. In fact, the percentage of Americans who are believers is higher than many industrialized nations.

But the survey raises an interesting point: Is being religious and being spiritual the same thing?

The study also suggests that in some ways Americans are becoming more spiritual. About six-in-ten adults now say they regularly feel a deep sense of “spiritual peace and well-being,” up 7 percentage points since 2007. And 46% of Americans say they experience a deep sense of “wonder about the universe” at least once a week, also up 7 points over the same period.

It’s an important question to consider because Pew singles out Millennials who aren’t religious.

The same dynamic helps explain the declines in traditional measures of religious belief and practice. Millennials – especially the youngest Millennials, who have entered adulthood since the first Landscape Study was conducted – are far less religious than their elders.

For example, only 27% of Millennials say they attend religious services on a weekly basis, compared with 51% of adults in the Silent generation. Four-in-ten of the youngest Millennials say they pray every day, compared with six-in-ten Baby Boomers and two-thirds of members of the Silent generation.

Only about half of Millennials say they believe in God with absolute certainty, compared with seven-in-ten Americans in the Silent and Baby Boom cohorts. And only about four-in-ten Millennials say religion is very important in their lives, compared with more than half in the older generational cohorts.

It’s possible, Pew says, that Millennials will “age” into religion. The older people get, the more interested they become in religion.

For example, Generation Xers, Baby Boomers and those in the Silent generation all have become somewhat more inclined in recent years to say they rely mainly on their religious beliefs when thinking about questions of right and wrong; they also are more likely to say they read scripture regularly and participate in prayer groups or scripture study groups on a frequent basis.

Baby Boomers and those in the Silent generation also have become more likely to say their religion is the “one true faith leading to eternal life.”

However, older Millennials have not become substantially more likely to participate in small-group religious activities or say they rely on religion for guidance on questions of right and wrong.

But the most fascinating element of the survey is the component that shows nearly all age groups have increased the percentage of those who experience “wonder” about the universe.

What does all of this really mean? That’s the problem, The Atlantic’s review of Robert Wuthnow’s new book, Inventing American Religion notes. Statistics try to impose neatness on what is essentially a “messy struggle with existence.”

Religion may affect people’s views on politics, but it’s often a guidebook for more immediate, tangible experiences—birth, death, love, relationships, the daily slog of life.

Sociologists may have legitimate academic interests in how these experiences play out across demographic groups, but “it has been mostly through polling, and polling’s argument,” Wuthnow argued, that the broader public has “now become schooled to think that it is interesting and important to know that X percentage of the public goes to church and believes in God.”

Another way to put it: Polling has become the only polite language for talking about religious experience in public life. Facts like church attendance are much easier to trade than messy views about what happens to babies when they die, or the nature of sin, or whether people have literal soul mates.

There’s an implicit gap between people’s private self-understanding of their own moral nature and the way those complex identities are reduced in the media and public-research reports, like the ones produced by Pew.

This is what makes religion polling different from political polling: A question about who a person might vote for is relatively straightforward. A question about whether he or she believes in heaven or an afterlife is not.

The Pew survey is important, the review acknowledges, although whether people attend church or believe in a god doesn’t capture the more private conversations about how we grapple with our existence and our struggle to know that which we cannot know.

Related: The Need To Believe: Where Does It Come From? (NPR)