With just a month left until Primary Election Day and four months to go until the mid-term elections, a sad reality is making itself more obvious for people who use the Internet to follow political news: This campaign season is one of the worst for innovation in political coverage.

While use of previous ideas is providing plenty of campaign coverage value, we’re hard-pressed to identify new significant apps, Web sites, or practices that could be a game-changer for political news coverage in 2010. Over the last ten years, the development of such tools was standard, possibly peaking in 2008. Many of those innovations have become so ingrained, that we don’t think about them much anymore. But something has happened: innovation has slowed considerably and we may go through the entire campaign cycle without a significant new tool.

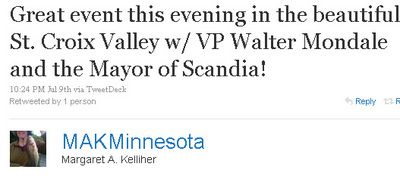

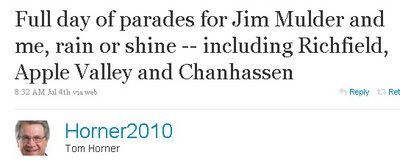

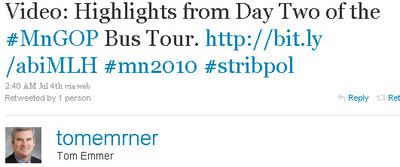

Twitter, perhaps, had the greatest possibility to change the relationship between candidate and voter, but it has yet to achieve anything close to its potential. Consider these typical tweets from gubernatorial candidates over the last week.

For a politician on Twitter, everyone is always happy and things are going great.

The dearth of political tools is most evident when you look at the history of the developing relationship between technology and politics.

2008

The St. Petersburg Times debuts PolitiFact, which “examines more than 750 political claims, separating rhetoric from truth to enlighten voters.” It was so game-changing that it won a Pulitzer in 2009. Other media (including MPR with its PoliGraph) have copied the idea. That’s a good thing.

Nate Silver, who made a name for himself analyzing baseball statistics, debuts fivethirtyeight.com, to use polling and other science to predict the election. It’s a hit. In 2010, he agrees to be absorbed by the New York Times.

Barack Obama mobilizes an online team and creates an “Obama community” to rally support for his presidential bid. He announces his selection of Joe Biden as his vice president running mate via text messaging. Obama’s free Obama08 app organized a person’s iPhone contacts to enable supporters to call friends located in important electoral districts. After he’s elected, some experts predict his large database of online supporters would change the way presidents seek support. The experts were wrong.

The Uptake provides citizen journalism with reports from Iowa. It would go on to become the go-to site for coverage of the Norm Coleman-Al Franken recount.

2007

CNN hosts the first YouTube debate.

2006

More candidates turn to online fundraising and add video capability to Web sites with the notion of removing the editorial filter of mainstream media.

But online video proves to be a two-edged sword for politicians as opponents begin following candidates. “Macaca moment” becomes a part of the language.

2004

A host of political blogs sprout around the presidential election, many fueled by disputes over the military careers of John Kerry and George W. Bush. The experts say the blogs, perhaps more than mainstream media, will influence political thought. The experts were right. Powerline wins Time’s Blog of the Year for its role in uncovering phony documents used by CBS News in examining President Bush’s military record.

Electoral-vote.com begins providing daily predictions of the electoral vote in the November election based on individual state polls.

2002

E*Democracy, an online-coordinated political community, harnesses a group of volunteers to work with the Minnesota Secretary of State to develop MyBallot.net, which allows people to enter their address and find out where they should vote, and provides them with links and sample ballots indicating what races are on the individual’s ballot.

MPR unveils Select A Candidate, a tool which matches potential voters with candidates who most closely match their views. In 2008, MPR made Select A Candidate available to other Web sites in the nation.

DailyKos is created, which mobilizes liberal Democrats.

2000

A group of former staffers at the Federal Elections Commission begins posting the campaign finance reports of candidates, making them searchable. The tool changes the game for monitoring money in politics. Other Web sites — the Center for Responsive Politics, for example — begin providing monitoring tools.

1999

Candidates post their campaign ads online, which also inaugurates the “fact checking” of campaign ads. Within a few years, candidates respond by producing ads more quickly, and stress image more than facts.

1998

The Minnesota Secretary of State’s office provides online election results. Over the course of the next decade, this developing technology would transfer election results to other media sites, much of which is then used to provide analytical tools.