For all of the Minnesota Supreme Court cases that I see in which justices try to figure out what the Minnesota Legislature intended when it passed a law, I rarely see the Legislature subsequently take up the law again.

Today, sort of, was an exception when a committee at the Minnesota Capitol considered whether to tighten the law that the court ruled on when it overturned the expulsion of a student for bringing a knife to school.

Ironically, it’s also a case in which the justices weren’t at all uncertain what the Legislature intended when it passed the Pupil Fair Dismissal Act in 1974.

The justices ruled that Alyssa Drescher posed no threat by bringing a knife to school (she says she used it to cut twine during her farm chores) because it was in her coat in her locker and she didn’t even know she had it. And the law allows expulsion for “’willful violation’ of a reasonableschool policy only if the student deliberately and intentionally violates the policy.” (See ruling)

The justices ruled that Alyssa Drescher posed no threat by bringing a knife to school (she says she used it to cut twine during her farm chores) because it was in her coat in her locker and she didn’t even know she had it. And the law allows expulsion for “’willful violation’ of a reasonableschool policy only if the student deliberately and intentionally violates the policy.” (See ruling)

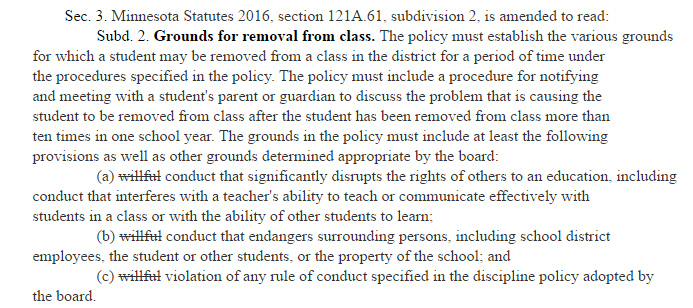

Now, a lawmaker wants to get rid of the word “willful.”

Rep. Ron Kresha, R-Little Falls, reportedly wasn’t even sold on his own bill, a pretty good indication that it’s probably dead.

It wouldn’t have made any difference to Alyssa Drescher. By the time the Supreme Court decided the case, she’d already graduated from high school in Wells, Minn., and missed her junior prom during the expulsion.

But Andrea L. Jepsen, with the School Law Center in St. Paul, who represented her in the case, recently cited another case in which a Northfield student faced expulsion for having an unloaded BB gun in his car. The school board opted not to expel the student, she wrote in Northfield News last month.

Districts try to get clever with this language, coyly changing it to argue they need not attempt to avert dismissal in cases where a student’s past behavior created some remote likelihood of danger. The “immediate danger” standard described in statute becomes the “mere potential for danger.” A forward-looking analysis becomes a retrospective one. Aside from resulting in a serious legal violation, these shenanigans harm students and damage schools’ integrity.

And to what end? The harm to students when districts dismiss students, regardless of the seriousness of their behavior or any mitigating circumstances, is virtually uncontroverted. So, too, is the science showing that the part of the brains of young people that controls self-regulation is still under construction. While districts remove students who engage in disruptive behavior in the belief that doing so will deter bad behavior in others, leaving a better school climate for the remaining students, those assumptions have been repeatedly shown to be false. As well, many researchers have identified the disproportionate use of school dismissal on children of color and children with disabilities.

At a hearing today, the lawyer who represented the school district in the Drescher case, said the Supreme Court’s ruling on the matter makes it easier for students to employ the “I forgot” defense, according to the Star Tribune.

The committee hearing the bill took no action, and the bill sponsor said he’d try to come up with some sort of compromise and, failing that, would just drop the effort.