A paper from George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, a generally anti-regulation organization, doesn’t try very hard to hide its distaste for people who don’t like airport noise.

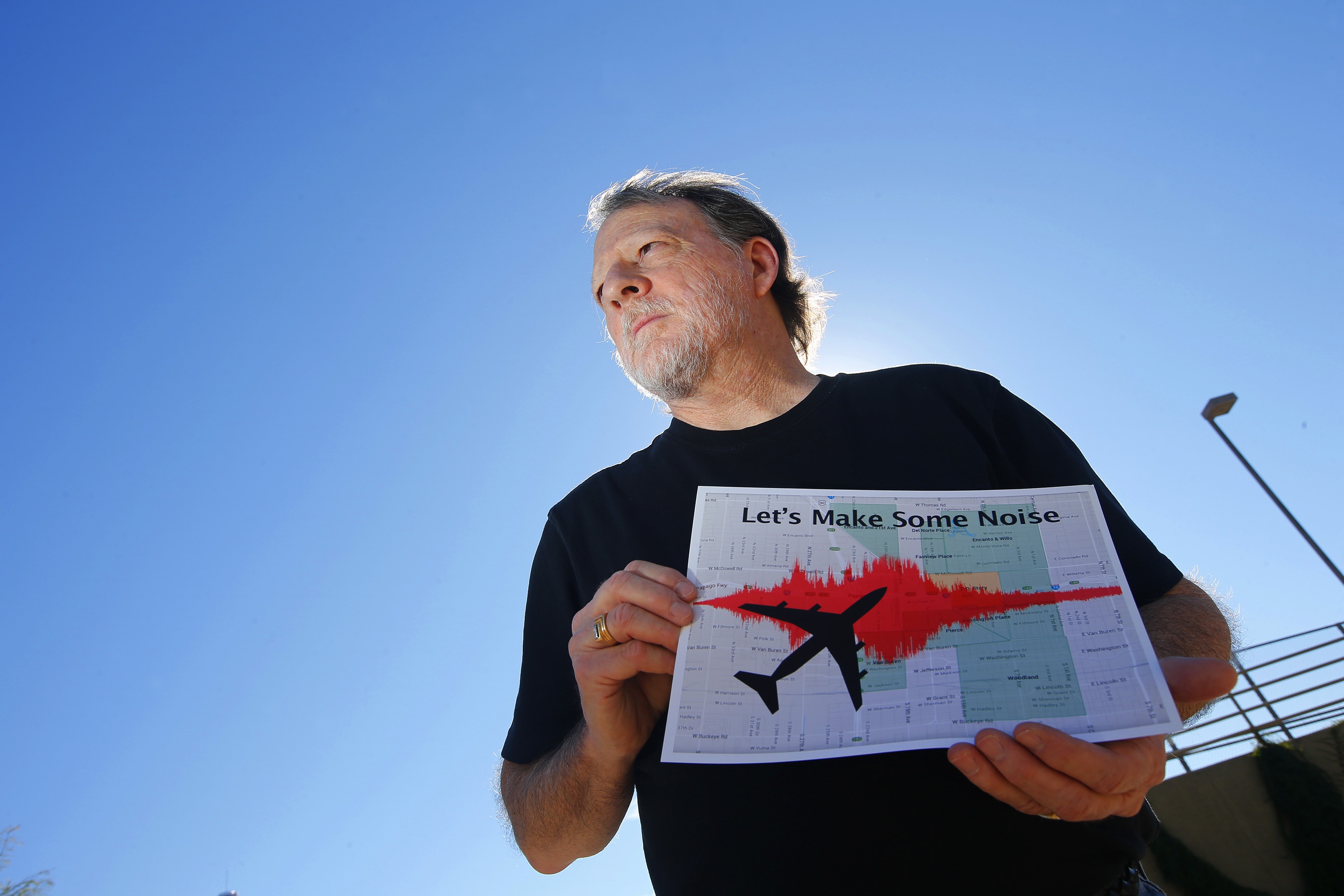

Eli Dourado and Raymond Russell tackle NIMBYism in their latest paper, claiming that complaints about airport noise come from a small number of people and disproportionately tilt noise abatement programs in a way that hinders the advancement of cheaper and faster commercial flight.

The researchers did not include Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport in their study, using two airports around Washington, DC., Denver, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco instead. But they clearly are applying their findings to the country.

Airport noise complaint data paints a startling picture. A handful of individuals are responsible for most of the noise complaints at most airports we examine. Some of these individuals do not appear to live particularly close to the airports to which they are complaining. For example, one individual in Strasburg, CO, 30 miles from Denver International Airport, complained 3,555 times in 2015, an average of 9.7 times per day. One individual in La Selva Beach, CA, about 55 miles from San Francisco International Airport, complained about airport noise 186 times during October 2015.

There are worrisome signs that this small, frustrated minority of citizens is affecting aviation policy. In recent decades, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has imposed progressively more stringent noise standards on aircraft operating in US airspace.13 While noise abatement is desirable, it can have significant costs—particularly on the fuel efficiency of aircraft—resulting not only in higher carbon emissions but also in higher ticket prices. It is troubling that a tiny but vocal group is potentially driving policy. While we do not have data on grievances lodged directly to the FAA or to members of Congress, it is probable that those airport noise complaints follow a similar pattern.

The researchers say noise abatement is already strict and say it would be “a mistake to allow the preferences of a vocal but minuscule minority of citizens, however sympathetic their circumstances, to impede much-needed improvements in aviation.”

Here’s their report.

It’s not the most diplomatic approach to the discussion, especially when a researcher for the Koch-funded institution calls the complainers “cranky” and “crazy”, something would turn back the clock of the noise-abatement issue in the Twin Cities, in which airport authorities have at least tried to be civil.

Kriston Capps’ assessment on The Atlantic’s CityLab site is only slightly less abrasive.

Even in places where one caller isn’t dialing in the overwhelming majority of complaints, the upper echelons tend to be dominated by a small number of vocal opponents. Only 42 households complained about noise in Denver, but 4 callers lobbied 4,653 of the complaints—96 percent of the total. (With most all of those coming from way out in Strasburg.) Five individuals made 61 percent of the 688 noise complaints that Portland International Airport received in 2015. (Possibly more complaints than the airport received for ripping up its carpet.)

Federal agencies can be terribly susceptible to the distorting effects of a few dedicated opponents of an ostensible public nuisance. For example, complaints to the Federal Communications Commission about indecency on television jumped from 350 in 2000 to some 240,000 in 2003. But 99 percent of these complaints were filed by the Parents Television Council, an advocacy group founded by conservative activist Brent Bozell. Account for all the automated copy-and-paste complaints, though, and it turns out that no one really cares about The Simpsons.

Capps acknowledges that people shouldn’t have to live in noisy flight corridors if they don’t want to. “The answer to this household dilemma, though, is not to move the airport.”

Of course, the proper response isn’t to move either. It’s to try to work out an equitable arrangement that at least seeks some common ground. That doesn’t happen by calling people “crazy.”

I’ve asked the MAC’s Noise Program Office for an assessment of the local complaints.

In August, the latest month for which data is available, 6,196 complaints were lodged from 308 people. Metrowide, about 12,000 complaints came from about 600 people (Data here). One person in Mounds View was responsible for all 51 complaints from that community. One person from Falcon Heights reported 26 separate complaints.

Archive: As Eden Prairie grows, an airport tries to get along with neighbors (NewsCut)

Lake Elmo airport shovels sand against neighbors’ tide (NewsCut)