In the 24 hours since we learned the first officer of a German airliner intentionally drove it into the French Alps, we’ve been told plenty about the mental health screening of pilots.

In the United States, a pilot needs a pilot certificate and a medical certificate to fly any aircraft, including commercial airliners. For airline pilots over 40,, it must be renewed every six months.

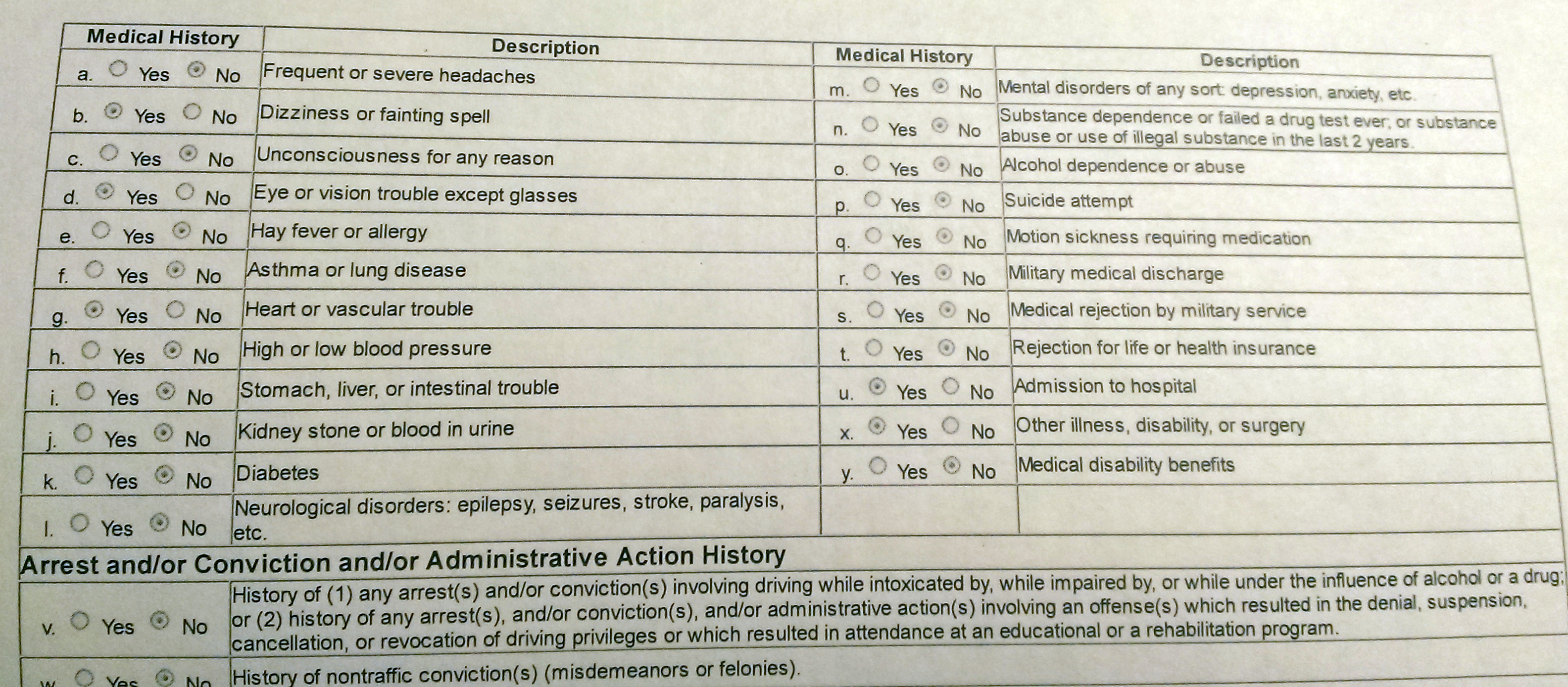

The Federal Aviation Administration form asks a couple dozen questions about medical history. Here’s the one I filled out for my last medical a year or so ago.

Below this section, the FAA asks for details on any visit to a health care provider in the previous term.

Answer “yes” to any question, or indicate any visit to a health care provider, and the FAA flight surgeon is going to probe deeper and, potentially, ground you. That’s an expensive pain in the neck for private pilots like me, but for a commercial pilot it could lead to the end of a career.

There’s a way to prevent this from happening: Don’t answer “yes” and don’t go to the doctor.

On more than one occasion, for example, I’ve been infirmed enough to need an ambulance, but delayed calling for one while I debated whether it was worth giving up flying. I currently fly on a “special issuance” after losing my medical certificate. Maintaining it is time consuming and expensive. I could’ve avoided it — maybe — by withholding some information on the FAA form.

For sure, there’s a penalty for lying on the form. The FAA could pull your ability to fly forever. But when a career is at stake, many pilots consider it worth it.

In aviation, the warning among pilots is always “don’t tell the flight surgeon anything.” The culture is distrustful of government in the first place and considers the FAA medical examiner “the enemy.”

This, of course, is counterproductive. The pilot is usually the first on the scene of a crash. But we’re talking a livelihood and even if commercial pilots suffer from the same maladies — mental and physical — as the rest of the population (they do), the FAA medical certificate procedure discourages seeking help.

In addition, many pharmaceuticals are banned medications under FAA regulations.

This is why some pilots flew drunk for years. Ask Joe Balzer, who was one of the three Northwest Airlines pilots who flew a DC-9 from Fargo to Minneapolis in March 1990. All three were hammered. Balzer went to prison.

Subsequently, the infamous flight led the airlines, the unions, and the FAA to coordinate programs that could get an alcoholic some help.

“First they can save their lives. Then they can save their careers,” he told me in a 2009 interview. He now encourages pilots to seek help. And airlines are more proactive in providing help these days.

But pilots remain suspicious that the FAA is a partner in these endeavors. A year or so ago, it tried to expand its reach by grounding overweight pilots — based only on their body-mass index — on the theory that they probably also suffer from sleep apnea and may be too tired to pilot an airplane. The pushback was immediate and the FAA rescinded its proposed rule, but a new rule was due to be released this month that allows pilots to keep flying while the doctor investigates their sleep habits.

For non-commercial pilots, efforts in Congress and at the FAA have restarted recently to get rid of the third-class medical certificate (the one for private pilots), and depend solely on self-monitoring. The FAA has generally resisted the initiatives — a lot of older pilots fly illegally rather than risk an official FAA grounding — and it’s unclear what effect the new spotlight on medical standards in the wake of the disaster in the Alps will have.

“I’m uncertain what more we should want or expect,” Patrick Smith writes on Ask the Pilot. “Pilots are human beings, and no profession is bulletproof against every human weakness. All the medical testing in the world, meanwhile, isn’t going to preclude every potential breakdown or malicious act.

For passengers, at certain point there needs to be the presumption that the men and women in control of your airplane are exactly the highly skilled professionals you expect them to be, and not killers in waiting.”

That reality probably won’t survive in the aftermath of the Germanwings murders. Uninformed media and political pressure generally exceeds a standard of reasonableness in matters like this, leading to new procedures that merely create the illusion of additional safety.