A new study suggests there is sexism in how we approach pending disaster.

Researchers at the University of Illinois reportedly have found that more people are killed by female-named hurricanes than male-named storms “simply because a storm with a feminine name is seen as less foreboding than one with a more masculine name.”

It’s all right there in today’s press release from the university:

“The problem is that a hurricane’s name has nothing to do with its severity,” said Kiju Jung, a doctoral student in marketing in the U. of I.’s College of Business and the lead author on the study.

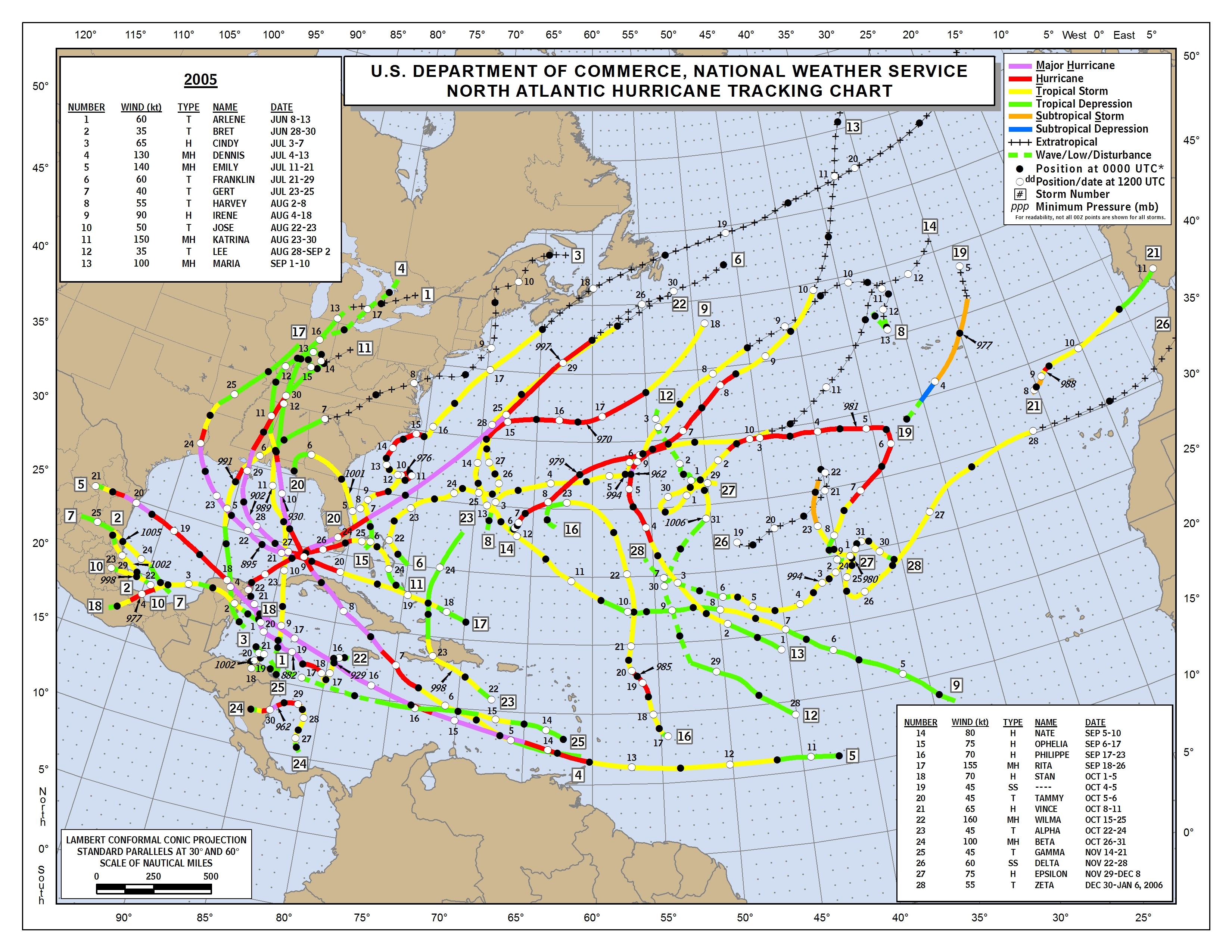

“Names are assigned arbitrarily, based on a predetermined list of alternating male and female names,” he said. “If people in the path of a severe storm are judging the risk based on the storm’s name, then this is potentially very dangerous.” The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined actual hurricane fatalities for all storms that made landfall in the U.S. from 1950-2012, excluding Hurricane Katrina (2005) and Hurricane Audrey (1957) because they were much deadlier than the typical storm.

The authors found that for highly damaging storms, the more feminine the storm’s name, the more people it killed. The team’s analysis suggests that changing a severe hurricane’s name from the masculine “Charley” to the feminine “Eloise” could nearly triple its death toll.

“In judging the intensity of a storm, people appear to be applying their beliefs about how men and women behave,” said Sharon Shavitt, a professor of marketing at Illinois and a co-author of the report. “This makes a female-named hurricane, especially one with a very feminine name such as Belle or Cindy, seem gentler and less violent.”

“The stereotypes that underlie these judgments are subtle and not necessarily hostile toward women – they may involve viewing women as warmer and less aggressive than men,” Shavitt said.

They said the study is “the first to demonstrate that gender stereotypes can have deadly consequences.”

The study doesn’t mention one possibly key factoid. Although they measured hurricanes over 60 years, only female-named hurricanes killed anyone for about half of that time because male names weren’t used until 1980.

The researchers said they factored that into their study and found the same results before and after 1980. But National Geographic isn’t buying it:

The fact is they couldn’t find a significant link between the femininity of a hurricane’s name and the damage it caused for either the pre-1979 set or the post-1979 one (and a “marginally significant interaction” of p=0.073 doesn’t really count). The team argues that splitting the data meant there weren’t enough hurricanes in each subset to provide enough statistical power. But that only means we can’t rule out a connection between gender and damage; we can’t soundly confirm one either.

And there’s one more. All hurricanes aren’t the same. People might not flee a hurricane, for example, because it’s barely a tropical storm.

And the male-female claim can’t be put to the test with any reliability.

In the year that Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, six hurricanes raced up the Mississippi delta. All were named after women. In fact, every hurricane that hit the U.S. that year was a female-named hurricane. Female-named hurricanes killed more people that year because only female-named hurricanes could kill anyone on land that year.