Joe Mauer and his wife are the proud parents of twin girls and good for them. He seems like a guy who has his head screwed on straight.

The Mauer twins will never lack for money or resources to get a head start in life. Neither, of course, will the future king of England, whom you may have heard was born and named this week. Again: good for them.

This week, though, has provided us with an opportunity to consider how incredibly lucky we are — or aren’t, depending — to be born to some parents and not others.

We are raised to believe that success in the world depends on our ability to work hard enough. But as the haves begin to put more distance between themselves and the have-nots, let’s take a moment to observe another truth: it comes down to dumb luck.

The odds of being the children of wealth are stacked higher than ever.

One in five children in America lives below the federal poverty line and almost one in two are poor or near poor, the American Pediatric Association Task Force on Childhood Poverty reported earlier this year in a study that was fairly well ignored, at least compared to the attention focused on babies this week.

It said:

Children are the poorest members of our society, a society that knows how to use policies and programs to raise its citizens out of poverty. Thirty five percent of seniors lived below the FPL [federal poverty line] in 1959, but due to programs like social security expansion and Medicare, only 9% of seniors are poor today. What the US does for seniors is clearly good; so why do we not also protect children from the life-altering effects of poverty?

The effects of poverty on children’s health and well-being are well documented. Poor children have increased infant mortality, higher rates of low birth weight and subsequent health and developmental problems, increased frequency and severity of chronic diseases such as asthma, greater food insecurity with poorer nutrition and growth, poorer access to quality health care, increased unintentional injury and mortality, poorer oral health, lower immunization rates, and increased rates of obesity and its complications.

Forty-nine percent of American babies born into poor families will be poor for at least half their childhoods, an Urban Institute study found. Among children who are not poor at birth, only 4 percent will be “persistently” poor as children.

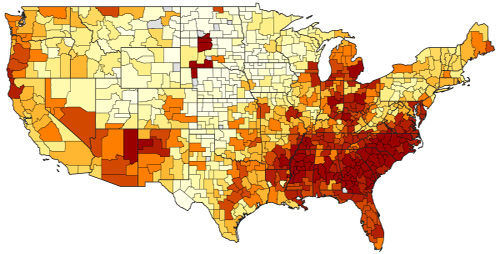

And this week a study showed it matters where you’re lucky enough to be born. The darker the color in this map, the greater the chance of being born into poverty:

The research suggests that moving to a more prosperous neighborhood or city could help kids, but (a) how can poor people afford to move and (b) that’s been tried before. The Moving for Opportunity program helped families move. It didn’t work, writes Evan Soltas at Bloomberg.

These findings led researchers to believe that it wasn’t the place, it was the family — a dispiriting conclusion that undermined the case for housing policies and challenged the idea that government can help give poor kids a real chance at success.

The Moving to Opportunity research isn’t in direct contradiction with the new work. With many of the moved children only in their 20s, we don’t yet know whether they’ll have higher-income careers. The earlier findings had suggested they would not. Now we have a reason to think such programs can make a difference in the lives of poor families. That’s worth celebrating.

Higher education has been widely recognized as a pathway out of poverty, but who can afford it? Tuition is going up faster than help to fund it.

The student loan program is in shambles. And there’s at least some evidence that attempts to make higher education more affordable for the poor have backfired.

None of these realities got much attention this week, or, really, any other week. They’re not likely to be fixed any time soon.

You’re either lucky, or you’re not.