I have, occasionally, accompanied a family member to someone’s funeral, listened to the eulogy, and left thinking I missed an opportunity by not knowing the person. Today’s online eulogies to former Pioneer Press editor Deborah Howell evoke the same feeling.

In the old “just the facts” style of “old media,” the news stories of her passing in New Zealand do not allow us to know her, only her accomplishments.

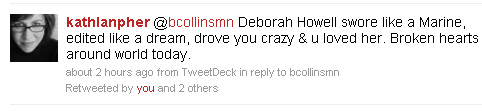

That’s where “new media” shines. Former colleague Katherine Lanpher, for example, tweeted me this wonderful description of Howell:

Typical Lanpher; a more beautiful tribute could not possibly be penned.

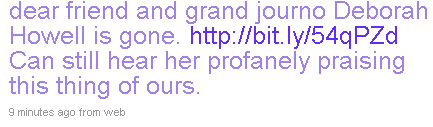

Former Twin Cities journalist David Carr tried:

Howell ended her career at the Washington Post. Today, the Comic Riffs blog remembers her love of comics, editorial cartoons, and the people who wrote them. Michael Cavna tells the Howell story of some editorial cartoonists who snuck into some parties at a political convention:

Which is why I took her advice. I called Luckovich, the great Atlanta Journal-Constitution cartoonist. Luckovich not only confirmed the story — he also filled in colorful details. Bottom line: Even with the most casual anecdote, Deb had gotten the story right.

Now, all my sources check out again: Deb was a pioneering editor, a consummate dogged journalist, an enormous supporter of newspaper cartooning and cartoonists and as big as Texas in her generosity and friendship.

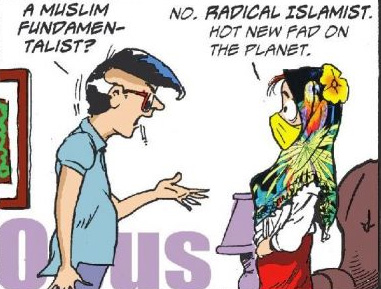

She was apparently a big fan of Opus. She had to explain once why this panel got rejected by the Post.

She held her fire until the last paragraph:

I think Post editors overreacted in killing the strips. Comics are meant to be artful, fun and provocative. The two strips were all of that and worth publishing. Let comics be comics.

P.S. Love that penguin!

Michael Calderone at Politico writes that Howell gave it as good as she got it:

As ombudsman, Howell wrote critically on the Post’s journalism, and at times, found herself on the receiving end of criticism. For instance, after writing that the Jack Abramoff scandal also involved Democratic politicians, Howell drew fire from liberal watchdogs and bloggers, resulting in the Post’s comments section briefly going down.

Still, Howell remained undeterred, writing after: “There is no more fervent believer in the First Amendment than I am, and I will fight for those e-mailers’ right to call me a liar and Republican shill with salt for brains. But I am none of those.”

Jeff Jarvis, writing at his Buzz Machine blog, suggested that Howell understood that in the new media landscape, the most informative tool is the one traditional journalists are most afraid of: their own voice:

I learned that Deborah had little fear of learning. I argue that we must all learn in public now — which means making mistakes and finding lessons and moving on. We online need to be more generous with others as they learn our ways. There’s no sense in replacing one orthodoxy with another. What we need instead is curiosity. That is what Deborah had.

More?

How about Steven A. Smith’s sweet remembrance upon Howell’s retirement just over a year ago:

Deborah has shown considerable courage herself through the years. I remember the fuss among readers and even advertisers when The Pioneer Press printed and then won a Pulitzer for “Aids in the Heartland,” one of the first stories anywhere to show that Aids was not just an urban plague. Deborah’s unflinching support of reporter Jacqui Banaszynski’s project led to truly groundbreaking journalism.

But on a more personal level, I owe Deborah for the single most important management lesson I ever received.

I was a mid-level city desk editor at The Pioneer Press at the time. I had been assigned an intern for the summer, a young woman who was to join my small team of reporters. For any number of reasons, the intern and I did not mesh. It was an ugly relationship. I couldn’t seem to get through to her, she legitimately disliked me. It happens. But at the time, I took it all personally.

Late one evening after a particularly contentious encounter, I threw up my hands. Impulsively, I typed out a note to Deborah telling her I was going to wash my hands of the problem, that I simply wasn’t going to work with this young lady any longer and that I sincerely hoped some other sucker would have more luck.

And I slipped it under Deborah’s office door.

In those days staffers would occasionally receive in their mail boxes so-called “blue notes,” handwritten notes on blue paper generally critical of something we had done, a mistake we had made, etc. Complimentary notes were on white paper, so that glimpse of blue in the mailbox sent a shiver down many an editor’s spine.

The morning after my temper tantrum, in response to my intemperate note, I found a Howell blue note in my box. “Take responsibility” is all it said.

By the way, it says something about the state of her former newspaper in the Twin Cities, that it gave her death only six weak paragraphs — eight sentences — of copy. I’d love to know what she’d think of that.