From the book table: An Extraordinary History of Objects

Tis the season for holiday gifts - and plenty of hard-bound goods have been arriving on the Daily Circuit book table as we get into the wintery days.

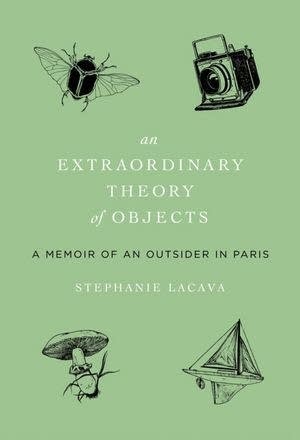

My favorite new discovery from the table this week is Stephanie LaCava's new book, An Extraordinary Theory of Objects (just released this Wednesday), which is truly a lovely book in every sense.

LaCava, who began her career as a fashion writer at Vogue, certainly created a beautiful little package with her book.

The narrative follows LaCava's unhappy childhood in France and the solace she takes in strange and pretty objects. Does it sound like a brief concept? It is. And the book itself comes in at only 177 pages. But it's charm is in the power of these little objects to help LaCava overcome her family's move to a strange new country, and the bout of extreme adolescent depression that follows.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Surrounding herself with tiny stones, figurines and garden oddities, LaCava describes the kind of comfort many of us find in having something weighty to hold on to. As she writes "Collecting information and talismans is a way of exercising magical control," which when you're a teenager, means more than anything.

Between the connected essays recounting her childhood and later life, the pages are dominated with beautiful black and white drawings of the items LaCava collects and - arguably more interesting - the little objects that she remembers encountering during the darker times in her life: her father's moustache, an old cardigan, a Dodo diorama from the Natural History Museum in Paris. With each drawing, LaCava includes a footnote to give the object its importance, although it is not simply an explanation. While the narrative of her essays is matter-of-fact and straight forward, these footnotes allow her to veer off on funny, wandering tangents full of bizarre historical facts. As the footnote to a glass eye she saw at a flea market recounts - "Elaborate hollow glass eyes began in Germany's Black Forest in 1832 when Ludwig Müller-Uri's young son lost his eye in an accident. Luckily, Müller-Uri happened to be a talented glassblower known for making realistic doll eyes by twisting strands of colored melted sand."

Admittedly, the first 20 pages left me a little adrift, unsure if I trusted the narrator's complaints (wouldn't we all actually love a childhood in France?), and self-diagnosed quirks. But as a person who also compulsively collects little things as I go about my day (I may or may not currently have two rocks in my wallet), I was moved forward by a desire to find more of LaCava's objects on the coming pages, and the strange histories of the pieces that come to serve as a quirky lens into LaCava's family and vision of herself. LaCava's memoir truly opens up in a tender way by the end of the story.

We all naturally like to collect the pretty things that we interact with, but often we don't stop to think about the role our collection of little things can play in our idea of self - and our past. An item doesn't have to live behind glass to serve as history, and reading LaCava's little book will make you think back on the things that stuck out in your childhood, and consider why they mattered.

-- Maddy Mahon, assistant producer